SQUATTER is built entirely from Ramona’s point of view: her humor, her fear, her confusion, and her private logic. The film doesn’t observe her from the outside; it inhabits her. That meant building a visual language that bends, buckles, and amplifies the world as she experiences it.

A CINEMA OF DISTORTION + CLARITY

The film moves between domestic realism and heightened, surreal intensity, mirroring the disorienting way violence functions inside families: sometimes numbingly ordinary, sometimes absurd, sometimes terrifying.

The aesthetic is intentionally unstable, folding realism into surrealism in order to approximate the fractured consciousness that forms under generational violence. We’re not interested in cataloging harm; we’re interested in its psychic topology — the way fear warps space, the way vigilance sharpens color, the way dread bends time into loops and false exits.

The film draws on the elastic subjectivity of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and the psychological ruptures of Fight Club, but its lineage also includes the domestic absurdism of Buñuel, the emotional precision of Lynne Ramsay, and the tonal tightrope of tragicomedy. What emerges is a world that is always slightly off-axis, where the internal leaks into the external without announcement.

The goal is not stylistic flourish; the goal is psychological fidelity. The audience doesn’t “watch” Ramona— they inhabit her, even when her perceptions become unreliable, comedic, or grotesque.

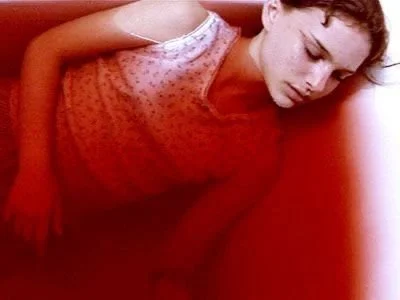

NERVOUS SYSTEM OVERLOAD

Ramona’s point of view shapes the film’s entire visual and emotional vocabulary: a world experienced from inside a nervous system running too hot, where desire, fear, instinct, and rage collide without hierarchy. Her body becomes the film’s primary instrument—breath dictating rhythm, adrenaline bending time, close-ups expanding into psychological landscapes. Small sensations register with seismic force; a glance, a gasp, a sprint become acts of survival rather than movement. The camera remains tethered to her internal weather, translating hyper-vigilance into cinema and revealing a consciousness that is perceptive, impulsive, darkly funny, and perpetually on the brink of rupture.

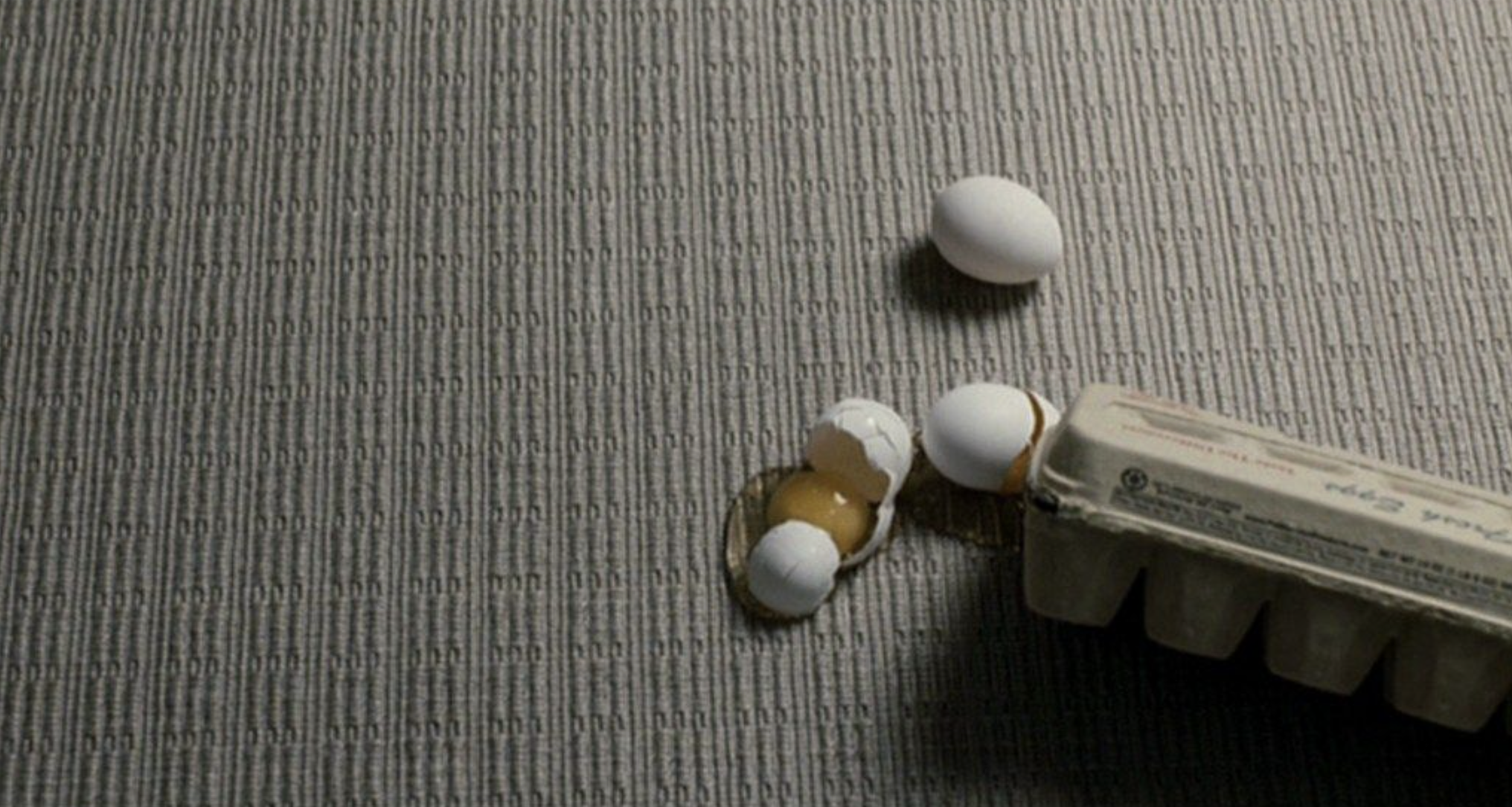

THE UNCANNY DOMESTIC

The domestic environment functions as a psychological architecture—rooms that present as orderly yet reveal their fractures under sustained attention. Every object carries contradiction: the pristine table that can’t disguise last night’s rupture, the latex gloves paired with a cigarette, the glasses of milk made uncanny by their stillness. Violence rarely appears cinematic from the inside; it manifests in crooked linens, quiet messes, and the subtle distortions of a space slightly out of alignment. The familiar becomes eerie, the safe becomes suspect, and ordinary objects behave like semiotic clues Ramona can sense but not yet decode. Production design here is not naturalism but emotional cartography: patterns repeating like generational habits, colors humming with tension, emptiness speaking louder than conflict. The house itself embodies the truth Ramona feels but cannot articulate.